In rural Kano, maternal mortality remains alarmingly high. Kolawole Omoniyi reports on how traditional birth attendants (TBAs) dominate childbirth practices due to limited access to skilled healthcare providers, while cultural beliefs and corruption hinder the implementation of the federal government's Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF).

In Kano, more than a few rural communities bear witness to the dreams of young lives and the hopes of new mothers being extinguished by the scourge of maternal mortality.

On the eve of this reporter's visit to Unguwarbai community in Ajingi Local Government Area (LGA) of Kano State, a 20-year-old Kamilu Samaina had lost her life in a tragic childbirth ordeal.

Samaina endured a 15-hour home labor under a Traditional Birth Attendant (TBA’s) care, only to succumb to postpartum hemorrhage after several delays in receiving adequate medical attention.

“The baby survived, but Samaina began to bleed heavily,” her brother, Idris Musa, said.

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), also known as heavy bleeding after giving birth, is a serious but treatable complication that can be life-threatening if not treated quickly by a doctor or nurse.

Samaina’s family became afraid and desperate for additional medical attention as the TBA couldn't stop the heavy bleeding. It took the family two frantic hours before getting a car to take her to Ajingi Cottage facility, which was 15 kilometers away.

Once there, she had to endure another two-hour wait before being attended to, only to be referred to another hospital, Gaya General Hospital.

It took them another hour to secure a good transportation. The delay proved fatal. Kamilu Samaina died in her brother’s arms, few steps from the car that was meant to convey her to Gaya.

"We took her to Habiba Kongoma's house (TBA) when she was not feeling fine. Kongoma gave her some herbs, which she took three times daily. She later gave birth after 15 hours of labor. The baby is alive and healthy, but she started bleeding. We spent two hours before getting a car to carry her to the Ajingi Cottage facility. We spent another two hours before they attended to us, and they later referred us to Gaya General Hospital.

“We spent another hour before getting a car to take us to Gaya hospital; we were carrying her to the car stand when she died in our hands," Idris Musa recounted the harrowing experience with a sad face.

Samaina’s family members during a condolence visit

A month barely passes without a heartbreaking update from Gurduba and Unguwarbai communities in Ajingi LGA. Pregnant women in these communities frequently die during or after childbirth, according to Yakubu Makama, chairman of the Gurduba Ward Development Committee (WDC).

"We've lost many lives; at least one pregnant woman dies every month, and sometimes we record two or three deaths in a month," Makama said.

Despite the presence of a health post in Samaina's community, and a fully equipped 12-year-old Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Gurduba, high maternal mortality rates persist.

The Gurduba PHC is part of the federal government's Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) program but remains largely ineffective due to staffing issues.

"The facility has labor rooms, a laboratory, pharmacy, male and female wards, consulting rooms, a pediatric ward, waiting rooms, wheelchairs, a standby generator, air conditioners, and staff accommodation, but no staff to take delivery," Makama said.

Abandoned labour room at Gurduba PHC

Makama also disclosed that a midwife hired by WDC members to work at the Gurduba PHC three years ago was fired by the Kano State Primary Health Care Management Board (KSPHCMB) a year later.

"With the coming of the BHCPF, we were able to employ Sheba Musa, a midwife, after nine years without one. She started taking child deliveries daily, but the Kano State Primary Health Care Management Board stopped her. We later wrote several letters to the board for her replacement without a single response."

Suleiman Sabin, Officer-in-Charge of Gurduba PHC, corroborated Makama's statement. Sabin, a trained Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW), disclosed that gender barriers further complicate the situation.

"I am a trained CHEW and currently studying Public Health at the university. I have taken countless deliveries in the past, but being a man, pregnant women in this area refuse my help due to religious and cultural beliefs," he said.

Despite initiatives like the BHCPF aimed at addressing maternal mortality in Kano, the state still contributes significantly to the national statistics on maternal deaths in Nigeria. Findings by this newspaper reveal that the increasing reliance on TBAs in rural and hard-to-reach areas due to limited access to skilled healthcare providers, standard maternal and child health services, and religious and cultural beliefs are responsible for a substantial proportion of these tragic deaths.

How TBAs contribute to maternal deaths in Kano

Infant and maternal deaths in Kano are alarmingly high, ranking among the worst in the country. In 2022, the state government reported a maternal mortality rate of 1,025 deaths per 100,000 live births. Additionally, a Nigeria Health Watch report in 2020 revealed that only 21.5 percent, approximately two out of ten, of deliveries in Kano State are attended by skilled birth attendants. Another report by the Development Research and Project Center (DRPC), titled "Kano State Health Indices," reveals that less than 50 percent of the urban population and less than 40 percent of the rural population have access to healthcare services.

Due to these significant gaps, residents particularly those in rural areas increasingly seek alternative measures, including Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs). In Kano, TBAs typically lack formal medical training and their knowledge is often based on traditional practices passed down through generations, which may not align with modern medical standards. While their services are often inexpensive, this gap in knowledge often leads to the mismanagement of complications during pregnancy and childbirth, significantly contributing to poor maternal outcomes.

Rahama Mohammed, a TBA in Unguwarbai, has been providing voluntary services for over 20 years, despite occasional complications leading to death.

“We (TBAs) are about 200 in this local government (Ajingi), and I have been helping pregnant women to deliver their babies for over twenty years. We would have recorded more deaths in this community if not for our efforts.

“We don’t charge them a dime; they usually give us whatever they can afford, like N200 and a mudu of grains, before or on the day of the naming ceremony. Some of the pregnant women die sometimes due to complications. I just heard that a woman died yesterday, and she was buried this morning," she said.

Amina Zuberu, another TBA in Gurduba, boast about their role in saving the lives of pregnant women in the community due to the lack of adequate medical personnel at the Gurduba PHC.

“People prefer to call us for child delivery because there is no woman who can take their delivery at the Gurduba facility. Apart from our culture and tradition, which prevents them from allowing male Officer-in-Charge (OIC) of the facility to take their deliveries, some of them cannot afford the hospital bills, so they prefer us,” she said.

Hajiya Zaihatu Ado, another TBA with two decades of experience in the Fagwalawa community, Dambatta LGA, confirmed they often collect little to no fee as they are only filling a gap created due to inefficiencies in the healthcare system. She said the motivation is not money but a desire to help.

Hajiya Zaihatu Ado

“We are many here and in other neighboring communities. People patronize us very well because we don’t charge them. They normally give us a mudu of grains with N200, but now that things are expensive, they pay N500 only.”

“We take most of the deliveries in this village day and night despite the distance between here and Fagwalawa Cottage PHC, which is about 15 kilometers. There was a time when the government trained us in Dambatta local government on best practices. After the training, they were supplying us with hand gloves and other materials for childbirth. But they later stopped giving us the materials, so we continued with our normal traditional practice. Sometimes, we refer our patients to Fagwalawa health facility whenever we have complications,” she disclosed.

TBA uses spiritual water for child delivery

The reliance on TBAs is even more pronounced in other settlements. In twelve settlements in Fagwalawa ward, including Tadeta, Larabar Takuya, Gangara, Jaba, Unguwar Gudu, Tsiko, Maiparo, Maliki, Gidan Dawa, Takuya Fulani, and Gidan Gago, residents rely solely on a TBA named Hussaini Hassana.

Hussaini Hassana, a sexagenarian, goes beyond traditional methods by claiming to use spiritual water for child delivery. Hassana's approach, while rooted in tradition lacks any basis in modern medicine and this could potentially complicate a birth requiring medical intervention.

“I learned delivery from my late mother years back. I do some recitations in water, rub the tummy of pregnant women with the water, and they will deliver shortly by God’s grace,” Hassana narrated.

Despite the limitations of her methods, Hassana stressed that she plays a critical role in the community.

"I am the only traditional birth attendant in Laraba and neighboring communities. My role includes assisting with the delivery of babies and cleaning both the mother and baby afterward. However, my major challenge is a lack of manpower. I need others to be trained so they can assist me because the job is demanding, and without additional help, many pregnant women may not receive the care they need if I'm unavailable.

Hussaini Hassana

Impact of female staff shortage, cultural beliefs on Kano’s maternal deaths

The situation is further complicated by cultural beliefs and the lack of 24-hour health services. Like the Gurduba PHC, many rural health facilities in Kano are without female skilled birth attendants, leading many pregnant women to seek the services of TBAs.

Suwera Habibu, 40, a mother of five, told our correspondent that she delivered all her children at home with the help of a TBA due to the absence of female staff at Gurduba PHC.

"Indeed, some pregnant women do pass away here, but we often attribute it to the will of God. Thankfully, that was not my fate. Although we have a hospital, the lack of a female worker means it is against our culture and tradition for a male to assist with deliveries. Consequently, some women who can afford transportation go to Ajingi Cottage, where more health personnel are available.

"For me, delivering at home was the only option because I couldn’t afford hospital fees. Truly they (TBAs) don’t charge pregnant women for child delivery, but they will ask you to buy some care products worth about N7,000. This is in addition to the N3,000 paid for transportation,” Habibu said.

Farida Salisu, a nursing mother said she prefers traveling from her place in Unguwarbai to another local government area due to the absence of female personnel at Gurduba health facility closest to her.

“I have six children; I delivered two at home and four at Gaya General Hospital in Gaya local government. The distance is about 40 km from Unguwarbai. Gurduba PHC, which is very close to us is like 3 km but there is no female worker in the facility and I can’t allow a male to take my delivery,” she said.

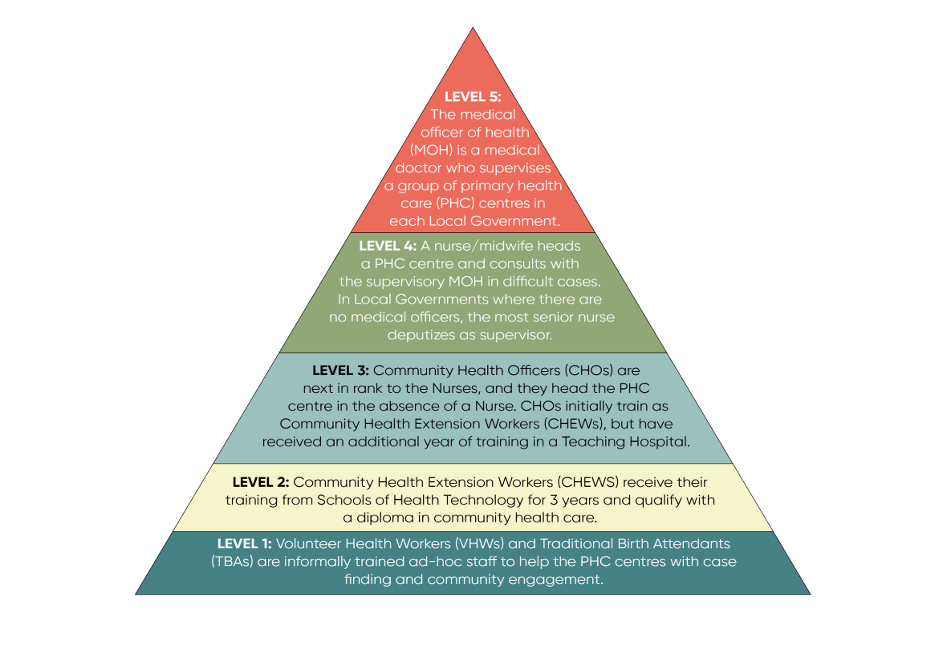

The shortage of staff, particularly female skilled birth attendants (SBAs) in Kano is a glaring example of the gender imbalance in critical health sector roles. This issue is particularly severe in rural areas, where many PHCs are led by Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), contrary to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) staffing requirements. According to the NPHCDA guideline, each PHC should have 24 staff members, a target that remains far from being met.

Hierarchical structure of primary healthcare (PHC) staffing in Nigeria

To address this issue, the president of the Nursing and Midwifery Alumni Association in Kano and Provost of Dansharif College of Nursing Sciences, Alhaji Sabo Machudo stressed that the state government is making efforts to train midwives, although recruitment challenges persist.

“We started producing midwives three years ago, but only about one percent of our graduates have secured jobs,” Machudo said.

“The challenge is not in the availability of midwives but in recruitment. The government should prioritize hiring these midwives and mandate private hospitals to do the same.”

However, the problem doesn’t end with recruitment; retaining female midwives in rural areas proves even more difficult due to marital obligations, poor infrastructure, and security concerns.

Dr. Fatima Adamu, Executive Director of Nana Women and Girls Empowerment Initiative, emphasized the need for a community-based approach to bridge this gap. She proposed a program where communities nominate married women for specialized midwifery training, with the understanding that they will return to serve locally after graduation.

“We introduced this program in Zamfara State with the support of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria, and it was successful,” Adamu explained.

“Graduates returned to their communities to serve. In one case, a husband initially supported his wife’s participation but later objected. The community’s Emir intervened, ensuring that she completed her training and continued serving as a midwife after the divorce.”

Irregularities persist despite BHCPF intervention

The federal government's Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) was established to improve universal health coverage and strengthen the national health system at primary healthcare level. However, despite the provision and release of funds for the program, its impact has been minimal. Allegations of corrupt practices at some of the benefiting facilities in Kano State have further hindered the initiative's effectiveness, findings have shown.

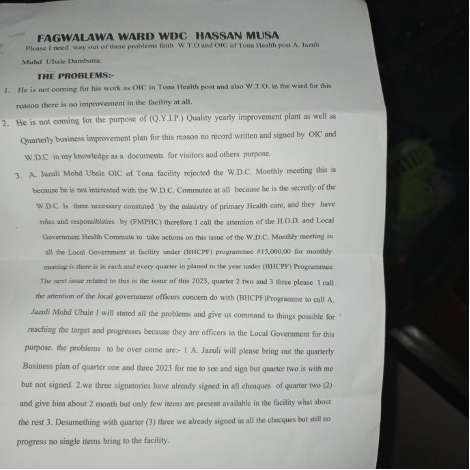

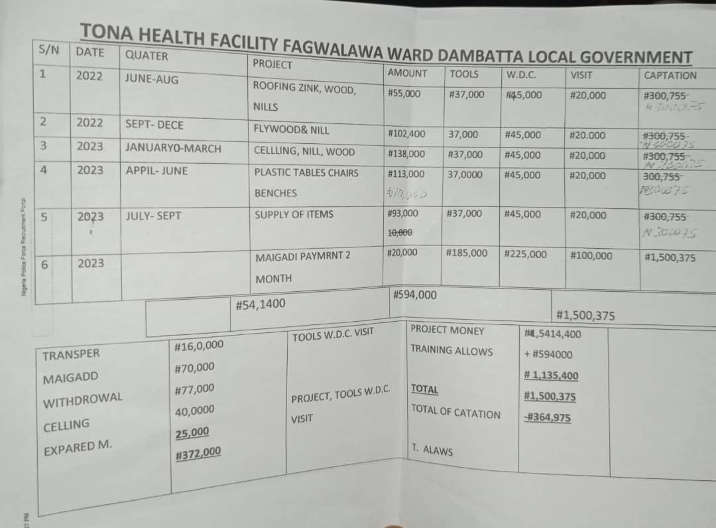

For instance, Hassan Musa, the Ward Development Committee (WDC) Chairman of Fagwalawa in Dambatta LGA, accused Jazuli Muhammed Ubale, the former Officer-In-Charge (OIC) of the Tona health post, of misappropriation.

“He never involved other WDC members. He would create the business plan himself and ask me and others who are signatories to the account to sign a cheque book. If I questioned his actions before signing the cheque, he would instigate the community members against me, claiming I was delaying their progress.

“We received funds for five consecutive quarters in this facility but have little to show for it. Out of over N1.5 million we got when he was in charge, he only accounted for about N500,000. He also bought some fake drugs. I took some of the drugs as evidence and handed them over to a supervisory committee that came here recently, but no action was taken thereafter. I wrote a letter of complaint to the board (KSPHCMB), but instead of him being sanctioned, he was promoted and transferred to Makoda LGA,” Musa said.

During a visit to the Tona health post, the facility was under lock and key. This reporter later caught up with the current OIC, Anas Garba. Garba also accused his predecessor of not relinquishing his role as a signatory to the BHCPF account adding that the facility can’t function efficiently and access the account without the presence of the former OIC.

“I went to the bank three times to change the status of the account three months ago, but the bank manager insisted I must come with Ubale for thumb printing. I have been calling him to let us go together, but he refused. Even the last drugs we procured from the Kano State Contributory Healthcare Management Agency (KACHMA), he was the person who signed the cheque,” Garba alleged.

Document of Executed Projects at Tona Facility

Tona Facility

Anas Muhammed Garba, OIC, Tona Health Post

Reacting, Ubale debunked all the allegations leveled against him by the WDC chairman, describing the latter as a perpetual complainant. “Don’t mind him; he has been lying against me. Everyone in the community knows him as a perpetual complainant,” he said.

Ubale, however, admitted to maintaining his role as a signatory to the BHCPF account three months after his transfer, promising to find time to go to the bank for rectification.

According to a source who is a top management staff at the Kano State Primary Healthcare Management Board (KSPHCMB), senior health staffers of LGAs consider junior roles such as OICs of the 484 BHCPF facilities juicy because of the fund at the disposal of the OIC.

“I have been in the health sector for a while now, and I have never seen a time when senior staff are asking to become facility in-charge, dropping their higher positions for this one because they know resources are going there,” the source said.

The irregularities in the implementation of BHCPF are not limited to just financial mismanagement. It also extends to the composition of the ward development committees (WDC), Although, Musa said for effective oversight that the ratio of male and female representatives in the committee is 60:40. However, none of the females are among the executive members therefore creating a significant oversight gap.

Musa stated that the reason for the skewed gender representation is because: “According to our tradition, women are not supposed to take a leadership role, and even their husbands will not allow them to do so, but they can participate.”

Hassan Musa

Compounding these existing problems is the suspension of the BHCPF program in December 2023, as confirmed by officials at the facilities visited by this newspaper. This suspension has further limited access to essential healthcare services.

While commending the BHCPF intervention in the community, Sabin expressed concern over the suspension of the program.

“The program was suspended six months ago. We used the previous funds released to execute some projects in our business plans as you can see, and we have not done anything this year,” he said.

Musa, Fagwalawa WDC Chairman, also confirmed the suspension of the BHCPF, adding that no reason was given.

Kano Govt. Reacts

The misalignment between how PHCs hire staff and the BHCPF guidelines has further complicated the already dire staffing situation in most healthcare facilities.

The Director of Planning at the Kano State Primary Healthcare Management Board (KSPHCMB), Dr. Bashir Sanusi said the board is taking steps to address the situation.

“For instance, in the entire Ajingi LGA, we don’t have a single trained midwife available for employment. We’ve informed the community that if they can provide one, she will be given an automatic job. We don’t want to send someone there only for them to flee,” he explained.

Dr. Sanusi also outlined the state government's short- and long-term strategies to ensure midwives remain at their assigned duty posts, especially in rural areas.

“In many cases, parents are hesitant to let their daughters travel far from home for education, and those who do come to the city often don’t want to return to their villages,” he noted. “To address this, our short-term plan is to grant automatic employment to midwife applicants from these remote areas, provided they have their certification and license. Applicants from the city, however, will undergo thorough screening.”